The Captain of the Push

1892

Henry Lawson

As the night was falling slowly down on city, town and bush,

From a slum in Jones’s Alley sloped the Captain of the Push;

And he scowled towards the North, and he scowled towards the South,

As he hooked his little finger in the corners of his mouth.

Then his whistle, loud and shrill, woke the echoes of the ‘Rocks’,

And a dozen ghouls came sloping round the corners of the blocks.

There was nought to rouse their anger; yet the oath that each one swore

Seemed less fit for publication than the one that went before.

For they spoke the gutter language with the easy flow that comes

Only to the men whose childhood knew the brothels and the slums.

Then they spat in turns, and halted; and the one that came behind,

Spitting fiercely on the pavement, called on Heaven to strike him blind.

Let us first describe the captain, bottle-shouldered, pale and thin,

For he was the beau-ideal of a Sydney larrikin;

E’en his hat was most suggestive of the city where we live,

With a gallows-tilt that no one, save a larrikin, can give;

And the coat, a little shorter than the writer would desire,

Showed a more or less uncertain portion of his strange attire.

That which tailors know as ‘trousers’—known by him as ‘bloomin’ bags’—

Hanging loosely from his person, swept, with tattered ends, the flags;

And he had a pointed sternpost to the boots that peeped below

(Which he laced up from the centre of the nail of his great toe),

And he wore his shirt uncollar’d, and the tie correctly wrong;

But I think his vest was shorter than should be in one so long.

And the captain crooked his finger at a stranger on the kerb,

Whom he qualified politely with an adjective and verb,

And he begged the Gory Bleeders that they wouldn’t interrupt

Till he gave an introduction—it was painfully abrupt—

‘Here’s the bleedin’ push, me covey—here’s a (something) from the bush!

Strike me dead, he wants to join us!’ said the captain of the push.

Said the stranger: ‘I am nothing but a bushy and a dunce;

‘But I read about the Bleeders in the Weekly Gasbag once;

‘Sitting lonely in the humpy when the wind began to “whoosh,”

‘How I longed to share the dangers and the pleasures of the push!

‘Gosh! I hate the swells and good ’uns—I could burn ’em in their beds;

‘I am with you, if you’ll have me, and I’ll break their blazing heads.’

‘Now, look here,’ exclaimed the captain to the stranger from the bush,

‘Now, look here—suppose a feller was to split upon the push,

‘Would you lay for him and fetch him, even if the traps were round?

‘Would you lay him out and kick him to a jelly on the ground?

‘Would you jump upon the nameless—kill, or cripple him, or both?

‘Speak? or else I’ll speak!’ The stranger answered, ‘My kerlonial oath!’

‘Now, look here,’ exclaimed the captain to the stranger from the bush,

‘Now, look here—suppose the Bleeders let you come and join the push,

‘Would you smash a bleedin’ bobby if you got the blank alone?

‘Would you break a swell or Chinkie—split his garret with a stone?

‘Would you have a “moll” to keep yer—like to swear off work for good?’

‘Yes, my oath!’ replied the stranger. ‘My kerlonial oath! I would!’

‘Now, look here,’ exclaimed the captain to the stranger from the bush,

‘Now, look here—before the Bleeders let yer come and join the push,

‘You must prove that you’re a blazer—you must prove that you have grit

‘Worthy of a Gory Bleeder—you must show your form a bit—

‘Take a rock and smash that winder!’ and the stranger, nothing loth,

Took the rock—and smash! They only muttered, ‘My kerlonial oath!’

So they swore him in, and found him sure of aim and light of heel,

And his only fault, if any, lay in his excessive zeal;

He was good at throwing metal, but we chronicle with pain

That he jumped upon a victim, damaging the watch and chain,

Ere the Bleeders had secured them; yet the captain of the push

Swore a dozen oaths in favour of the stranger from the bush.

Late next morn the captain, rising, hoarse and thirsty from his lair,

Called the newly-feather’d Bleeder, but the stranger wasn’t there!

Quickly going through the pockets of his ‘bloomin’ bags,’ he learned

That the stranger had been through him for the stuff his ‘moll’ had earned;

And the language that he muttered I should scarcely like to tell.

(Stars! and notes of exclamation!! blank and dash will do as well).

In the night the captain’s signal woke the echoes of the ‘Rocks,’

Brought the Gory Bleeders sloping thro’ the shadows of the blocks;

And they swore the stranger’s action was a blood-escaping shame,

While they waited for the nameless, but the nameless never came.

And the Bleeders soon forgot him; but the captain of the push

Still is ‘laying’ round, in ballast, for the nameless ‘from the bush.’

The Rocks Push was a notorious gang, which dominated the The Rocks area of Sydney, Australia from 1870s to the end of the 1890s. In its day it was referred to as The Push, a title which has since come to be more widely used for the Sydney Push.

The gang were engaged in running warfare with other Sydney gangs of the time such as the Straw Hat Push, the Glebe Push, the Argyle Cut Push, the Forty Thieves from Surry Hills and the Gibb Street Mob. They conducted such crimes as theft, assault and battery against police and pedestrians in the Rocks area. Female members of the Push would entice drunks and seamen into dark areas to be assaulted and robbed by the gang.

Australian authors of the time mentioned the Push in various of their works.

A poem called Bastard from the Bush, often attributed to Henry Lawson, describes (in vivid and colourful language) a meeting between a "Captain" of the Push and the "Bastard from the Bush". Banjo Paterson, in In Push Society, describes a group of tourists who go to visit the Rocks Push, and paints the following picture of the appearance of the gang members:

Wiry, hard-faced little fellows, for the most part, with scarcely a sizeable man amongst them. They were all clothed in “push” evening dress—black bell-bottomed pants, no waistcoat, very short black paget coat, white shirt with no collar, and a gaudy neckerchief round the bare throat. Their boots were marvels, very high in the heel and picked out with all sorts of colours down the sides.

Paterson also said, addressing Lawson in In Defence of the Bush:

You had better stick to Sydney and make merry with the "push",

For the bush will never suit you, and you'll never suit the bush.

One of the most famous haunts of the Rocks Push was Harrington Place, also known as the "Suez Canal" (supposedly a pun on "sewers"), one of the most unsavoury places in Sydney in its time.

During the period when the Rocks Push was active, such gang members were also known as "larrikins", but their behaviour bore little in common with larrikinism as it is commonly understood today.

Wikipedia

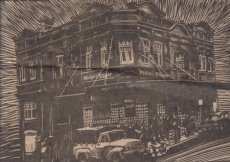

The Rocks, c. 1900, from NSW Government Records - lots of great photos.

See also Picture Australia and State Library, Victoria.

Henry Lawson

As the night was falling slowly down on city, town and bush,

From a slum in Jones’s Alley sloped the Captain of the Push;

And he scowled towards the North, and he scowled towards the South,

As he hooked his little finger in the corners of his mouth.

Then his whistle, loud and shrill, woke the echoes of the ‘Rocks’,

And a dozen ghouls came sloping round the corners of the blocks.

There was nought to rouse their anger; yet the oath that each one swore

Seemed less fit for publication than the one that went before.

For they spoke the gutter language with the easy flow that comes

Only to the men whose childhood knew the brothels and the slums.

Then they spat in turns, and halted; and the one that came behind,

Spitting fiercely on the pavement, called on Heaven to strike him blind.

Let us first describe the captain, bottle-shouldered, pale and thin,

For he was the beau-ideal of a Sydney larrikin;

E’en his hat was most suggestive of the city where we live,

With a gallows-tilt that no one, save a larrikin, can give;

And the coat, a little shorter than the writer would desire,

Showed a more or less uncertain portion of his strange attire.

That which tailors know as ‘trousers’—known by him as ‘bloomin’ bags’—

Hanging loosely from his person, swept, with tattered ends, the flags;

And he had a pointed sternpost to the boots that peeped below

(Which he laced up from the centre of the nail of his great toe),

And he wore his shirt uncollar’d, and the tie correctly wrong;

But I think his vest was shorter than should be in one so long.

And the captain crooked his finger at a stranger on the kerb,

Whom he qualified politely with an adjective and verb,

And he begged the Gory Bleeders that they wouldn’t interrupt

Till he gave an introduction—it was painfully abrupt—

‘Here’s the bleedin’ push, me covey—here’s a (something) from the bush!

Strike me dead, he wants to join us!’ said the captain of the push.

Said the stranger: ‘I am nothing but a bushy and a dunce;

‘But I read about the Bleeders in the Weekly Gasbag once;

‘Sitting lonely in the humpy when the wind began to “whoosh,”

‘How I longed to share the dangers and the pleasures of the push!

‘Gosh! I hate the swells and good ’uns—I could burn ’em in their beds;

‘I am with you, if you’ll have me, and I’ll break their blazing heads.’

‘Now, look here,’ exclaimed the captain to the stranger from the bush,

‘Now, look here—suppose a feller was to split upon the push,

‘Would you lay for him and fetch him, even if the traps were round?

‘Would you lay him out and kick him to a jelly on the ground?

‘Would you jump upon the nameless—kill, or cripple him, or both?

‘Speak? or else I’ll speak!’ The stranger answered, ‘My kerlonial oath!’

‘Now, look here,’ exclaimed the captain to the stranger from the bush,

‘Now, look here—suppose the Bleeders let you come and join the push,

‘Would you smash a bleedin’ bobby if you got the blank alone?

‘Would you break a swell or Chinkie—split his garret with a stone?

‘Would you have a “moll” to keep yer—like to swear off work for good?’

‘Yes, my oath!’ replied the stranger. ‘My kerlonial oath! I would!’

‘Now, look here,’ exclaimed the captain to the stranger from the bush,

‘Now, look here—before the Bleeders let yer come and join the push,

‘You must prove that you’re a blazer—you must prove that you have grit

‘Worthy of a Gory Bleeder—you must show your form a bit—

‘Take a rock and smash that winder!’ and the stranger, nothing loth,

Took the rock—and smash! They only muttered, ‘My kerlonial oath!’

So they swore him in, and found him sure of aim and light of heel,

And his only fault, if any, lay in his excessive zeal;

He was good at throwing metal, but we chronicle with pain

That he jumped upon a victim, damaging the watch and chain,

Ere the Bleeders had secured them; yet the captain of the push

Swore a dozen oaths in favour of the stranger from the bush.

Late next morn the captain, rising, hoarse and thirsty from his lair,

Called the newly-feather’d Bleeder, but the stranger wasn’t there!

Quickly going through the pockets of his ‘bloomin’ bags,’ he learned

That the stranger had been through him for the stuff his ‘moll’ had earned;

And the language that he muttered I should scarcely like to tell.

(Stars! and notes of exclamation!! blank and dash will do as well).

In the night the captain’s signal woke the echoes of the ‘Rocks,’

Brought the Gory Bleeders sloping thro’ the shadows of the blocks;

And they swore the stranger’s action was a blood-escaping shame,

While they waited for the nameless, but the nameless never came.

And the Bleeders soon forgot him; but the captain of the push

Still is ‘laying’ round, in ballast, for the nameless ‘from the bush.’

The Rocks Push was a notorious gang, which dominated the The Rocks area of Sydney, Australia from 1870s to the end of the 1890s. In its day it was referred to as The Push, a title which has since come to be more widely used for the Sydney Push.

The gang were engaged in running warfare with other Sydney gangs of the time such as the Straw Hat Push, the Glebe Push, the Argyle Cut Push, the Forty Thieves from Surry Hills and the Gibb Street Mob. They conducted such crimes as theft, assault and battery against police and pedestrians in the Rocks area. Female members of the Push would entice drunks and seamen into dark areas to be assaulted and robbed by the gang.

Australian authors of the time mentioned the Push in various of their works.

A poem called Bastard from the Bush, often attributed to Henry Lawson, describes (in vivid and colourful language) a meeting between a "Captain" of the Push and the "Bastard from the Bush". Banjo Paterson, in In Push Society, describes a group of tourists who go to visit the Rocks Push, and paints the following picture of the appearance of the gang members:

Wiry, hard-faced little fellows, for the most part, with scarcely a sizeable man amongst them. They were all clothed in “push” evening dress—black bell-bottomed pants, no waistcoat, very short black paget coat, white shirt with no collar, and a gaudy neckerchief round the bare throat. Their boots were marvels, very high in the heel and picked out with all sorts of colours down the sides.

Paterson also said, addressing Lawson in In Defence of the Bush:

You had better stick to Sydney and make merry with the "push",

For the bush will never suit you, and you'll never suit the bush.

One of the most famous haunts of the Rocks Push was Harrington Place, also known as the "Suez Canal" (supposedly a pun on "sewers"), one of the most unsavoury places in Sydney in its time.

During the period when the Rocks Push was active, such gang members were also known as "larrikins", but their behaviour bore little in common with larrikinism as it is commonly understood today.

Wikipedia

The Rocks, c. 1900, from NSW Government Records - lots of great photos.

See also Picture Australia and State Library, Victoria.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home