Sex and Anarchy - the life and death of the Sydney Push

Like the grasshopper in the fable, they lazed in the sun or in the gloom of a hotel bar, gambling, drinking, fornicating and endlessly talking. Though they had a critique for every aspect of society, they had no remedies. They produced dozens of argumentative little magazines, but they created hardly any art, film or music. They were proud of their lack of illusions - their dedication to the truth seemed bracing to some, and brutal to others. They appeared to have no avarice, and they opposed violence of any sort. They could have been Zen saints dedicated to the life of contemplation and non-action, except for their sloth, lust, and jealousy. They were the Sydney "Push", a loose and changing group of bohemian intellectuals, university lecturers, adventurous secretaries, journalists, gamblers, writers, free-thinking businessmen and students.

They formed in the turmoil of the 1940s, and flourished during the conservative 1950s. They were still a force in the early 1960s, but as the decade progressed and Australian society became freer and more tolerant, their distinctiveness and their importance faded.

Eventually many of the younger members moved out of the pubs and into the streets. They attacked censorship, they fought on behalf of feminism, and they protested against the Vietnam War, corrupt police, and rapacious urban developers. The older Push philosophers disapproved of this descent into direct action, with its inevitable bargains, concessions and compromises, but they were left talking to empty chairs...

As Coombs points out, the Push ideals are full of contradictions. For a start, the Push was a Leftist movement that did not believe in the goals of the Left, and they refused to be pigeon-holed politically. They took their beliefs from a wide range of philosophers and thinkers. Wilhelm Reich pushed Freud's sexual revolution to the edge of lunacy. Max Nomad asserted the need for permanent protest, but then the Italian philosopher Pareto convinced them that a revolution only brings to the surface another power elite, and Michels propounded the "iron law of oligarchy", that even democracies produce power elites, and do so inevitably. Where could they turn, except to the pub?

Their centre was Sydney, and their philosophy didn't travel well, or find acolytes in other cities. Germaine Greer in 1959 and Wendy Bacon in 1966 had to move from Melbourne to Sydney to discover the Push. It had no influence overseas.

Margaret Fink has called them "a dreary lot who wore dreary clothes, drank in dreary pubs and lived in dreary dwellings with nothing on the walls." True - Push people had little liking for art. To many of them, the creative life was woolly and lacking in intellectual rigour. Their taste in music was also a blank: folk songs and "trad jazz" was their idea of fun, and the rich delights of modern jazz and rock'n'roll were lost on them.

Women were treated as equals, in the male-dominated Push. They were expected to swear, fornicate freely, and drink in the public bar with the men (forbidden in most Sydney hotels until the late 1960s). But the focus on sex and status meant that when they had children, they lost their place at the bar. Nor were they encouraged to address political discussion groups, or to develop a career. The feminism of the late 1960s and early 1970s encouraged many of these women to grow and develop, and to work for success in their field. The feminist women in this book stand out as achievers, though it would seem they had to leave or outgrow the Push to do their best work - Wendy Bacon, Eva Cox, Germaine Greer, Lillian Roxon, Lynne Segal, and many others.

And for many of the men, the price of success in the Push was relative lack of success in their life outside it. This wasn't the case in similar movements overseas: the French Existentialists, the American beats, the English "Angry Young Men" of the 1950s all produced industrious, successful and famous writers and thinkers. Why didn't we?

Coombs puts her finger on the cultural psychology behind it: achievement requires ambition and dedicated effort, and ambition is still regarded by many Australians with suspicion. Art was for sissies, business was tainted with capitalism, and in politics, "careerism" was a dirty word. I feel this "futilitarianism" began with our convict past: if you tried to get on, you had to side with the English ruling class, and before long your fellow-convicts as well as your gaolers put you back in your place.

It's easy to criticise the Push for failing to achieve anything tangible, but to oppose conventional morality and politics was not easy in the 1950s. It should be pointed out that, as children, the people of the Push were taught to salute the flag at the weekly school assembly, to attend Scripture classes once a week even in state-run schools, and to stand for the national anthem and the image of the Queen of England at the start of every session at the movies - or the "pictures" as they were called then. For all their faults, it should be remembered that they were better people in many ways - more frank and honest, more socially aware and concerned - than those who chose the way of conformity and the compromises and hypocrisy that went with it...

- This is an excerpt from poet John Tranter's review of Anne Coombs' Sex and Anarchy

They formed in the turmoil of the 1940s, and flourished during the conservative 1950s. They were still a force in the early 1960s, but as the decade progressed and Australian society became freer and more tolerant, their distinctiveness and their importance faded.

Eventually many of the younger members moved out of the pubs and into the streets. They attacked censorship, they fought on behalf of feminism, and they protested against the Vietnam War, corrupt police, and rapacious urban developers. The older Push philosophers disapproved of this descent into direct action, with its inevitable bargains, concessions and compromises, but they were left talking to empty chairs...

As Coombs points out, the Push ideals are full of contradictions. For a start, the Push was a Leftist movement that did not believe in the goals of the Left, and they refused to be pigeon-holed politically. They took their beliefs from a wide range of philosophers and thinkers. Wilhelm Reich pushed Freud's sexual revolution to the edge of lunacy. Max Nomad asserted the need for permanent protest, but then the Italian philosopher Pareto convinced them that a revolution only brings to the surface another power elite, and Michels propounded the "iron law of oligarchy", that even democracies produce power elites, and do so inevitably. Where could they turn, except to the pub?

Their centre was Sydney, and their philosophy didn't travel well, or find acolytes in other cities. Germaine Greer in 1959 and Wendy Bacon in 1966 had to move from Melbourne to Sydney to discover the Push. It had no influence overseas.

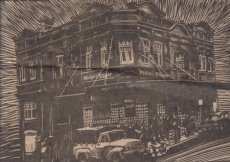

Margaret Fink has called them "a dreary lot who wore dreary clothes, drank in dreary pubs and lived in dreary dwellings with nothing on the walls." True - Push people had little liking for art. To many of them, the creative life was woolly and lacking in intellectual rigour. Their taste in music was also a blank: folk songs and "trad jazz" was their idea of fun, and the rich delights of modern jazz and rock'n'roll were lost on them.

Women were treated as equals, in the male-dominated Push. They were expected to swear, fornicate freely, and drink in the public bar with the men (forbidden in most Sydney hotels until the late 1960s). But the focus on sex and status meant that when they had children, they lost their place at the bar. Nor were they encouraged to address political discussion groups, or to develop a career. The feminism of the late 1960s and early 1970s encouraged many of these women to grow and develop, and to work for success in their field. The feminist women in this book stand out as achievers, though it would seem they had to leave or outgrow the Push to do their best work - Wendy Bacon, Eva Cox, Germaine Greer, Lillian Roxon, Lynne Segal, and many others.

And for many of the men, the price of success in the Push was relative lack of success in their life outside it. This wasn't the case in similar movements overseas: the French Existentialists, the American beats, the English "Angry Young Men" of the 1950s all produced industrious, successful and famous writers and thinkers. Why didn't we?

Coombs puts her finger on the cultural psychology behind it: achievement requires ambition and dedicated effort, and ambition is still regarded by many Australians with suspicion. Art was for sissies, business was tainted with capitalism, and in politics, "careerism" was a dirty word. I feel this "futilitarianism" began with our convict past: if you tried to get on, you had to side with the English ruling class, and before long your fellow-convicts as well as your gaolers put you back in your place.

It's easy to criticise the Push for failing to achieve anything tangible, but to oppose conventional morality and politics was not easy in the 1950s. It should be pointed out that, as children, the people of the Push were taught to salute the flag at the weekly school assembly, to attend Scripture classes once a week even in state-run schools, and to stand for the national anthem and the image of the Queen of England at the start of every session at the movies - or the "pictures" as they were called then. For all their faults, it should be remembered that they were better people in many ways - more frank and honest, more socially aware and concerned - than those who chose the way of conformity and the compromises and hypocrisy that went with it...

- This is an excerpt from poet John Tranter's review of Anne Coombs' Sex and Anarchy

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home